ECM.

My instincts after years of purchasing the label’s albums was always that the E would have stood for European, and the M stood for music. While I was half-right there, I had no clue as to what the C was for. I was leaning towards “continental” as I had thought the aim of the label’s output was to keep the artistry largely to those from “on the continent” of Europe. Still, it did seem redundant.

What does it stand for, then? Edition of Contemporary Music.

Much of the confusion for me came from the origins of ECM Records. The label was founded in 1969 by Manfred Eicher, Karl Egger, and Manfred Scheffner, all of whom are German, and are based out of Munich to this day. Then again, the first album ECM released was Free at Last by pianist Mal Waldron, recorded on November 29, 1969. This fact should have broke my (or others’) expectations right from the beginning as to what the label’s acronym means. The first few years of albums included those of several non-Europeans such as Marion Brown, Barre Phillips, Paul Bley, and Robin Kenyatta. Also, Eicher stresses his American influences repeatedly, such as in this Jazz.com interview where he name-checks Birth of the Cool by Miles Davis as an early favourite. Therefore, it would make perfect sense for his label to have a global scope, especially one where jazz is its major focus. Record with who you like regardless of where they happen to live or file their taxes.

I can’t spot much information about Karl Egger, and Manfred Scheffner’s time with ECM seemed relatively brief based on his discography (he died in 2019), which leaves Eicher as the central figure that kept this label going over the years. Eicher is said to have sat in the producer’s chair for every release on that label, with very few exceptions (such as Free at Last, which is credited to Scheffner, though Eicher supervised/engineered). No matter the capacity of his involvement on these albums, given that the label has over 1700 releases, that is a mind-blowing figure! Doing some quick math, let’s simply go with his 1459 production credits (as of December 10th) that are listed on Discogs. Across what has now been around 55 years when rounding up, that is roughly the equivalent of 26 per year or around 2 per month. Jazz sessions can run rather quickly depending on the artist, where studio time rarely spans more than a few weeks, and virtually never longer than one month. It’s a pace that does sound achievable, that is, if you don’t take any days off. Listening to a guy like pianist András Schiff from this 2019 interview, his familiarity with recording, right down to the slightest change in microphone placement, sounds so considerate to the point it became instinctual. In a 2015 discussion, bassist Gary Peacock commended him for being the one producer he worked with that had truly musical ears, with great emphasis placed on the sound of each instrument. A man doesn’t garner such praise if he’s merely cutting corners to navigate an evidently tight recording schedule.

I don’t plan on using this write-up to be a history-spanning piece on the label because I am nowhere near qualified enough to tell it. Besides, it has been covered to a great degree in other outlets. There are also sub-divisions and sub-labels under the ECM umbrella that I’ve yet to explore myself, particularly The New Series, which largely showcases contemporary classical musicians. That’s part of what I love about this label, the depth, not to mention its longevity, is unlike many independent record labels. Though I am familiar with a good amount of the label’s offerings (my last count only has around 40 in my personal collection), it’s thrilling to know that there is always going to be something in their back catalog for me to discover down the line. You could call it a safety net as I take the branding as a guarantee of quality.

Much of my limited knowledge of the label’s history comes from a special 50th anniversary issue of Down Beat magazine from November 2019. I’d recommend you read the article in its entirety if you can track it down, but one quote from it that jumped out to me relates to the philosophical nature of the label, or perhaps more so of Eicher if the two can be separated.

“It’s all about curiosity. It begins that way and I am still pursuing that. I am always searching for new sounds.”

That seems to be a very typical thing for the head of a record label to say, but coming from one that is largely jazz, I can believe this as being more than just a boilerplate quote. In contrast to rock music (admittedly the genre that makes up the biggest share of my collection), jazz utilizes significantly more combinations in musicians and band structure, which in turn provides a different medium through which melody, harmony, rhythm, etc. is filtered. If you were to begin your journey into jazz music with bands led by guitar players (let’s go with John Abercrombie or Terje Rypdal to keep it in the ECM family), as your tastes expand to appreciate ensembles headed by pianists (Paul Bley, Steve Kuhn) or wind players (Charles Lloyd, Lester Bowie), you’ll see great variance in how they delegate different parts and afford freedom of expression to their band mates. In my experience, I find such approaches to be far more varied in jazz than in rock or other more popular form of music. While it is true that there is still a good deal of ways in how you can take typical rock instrumentation (vocals, guitar, bass, drums, and sometimes keyboards) and get unique sounds, I find that rock-based record labels tend to specialize in certain categories (hardcore punk, death metal, etc.) whereas a jazz label like ECM will carry artists that spread through different sub-genres or styles (bop, avant-garde, fusion, etc.).

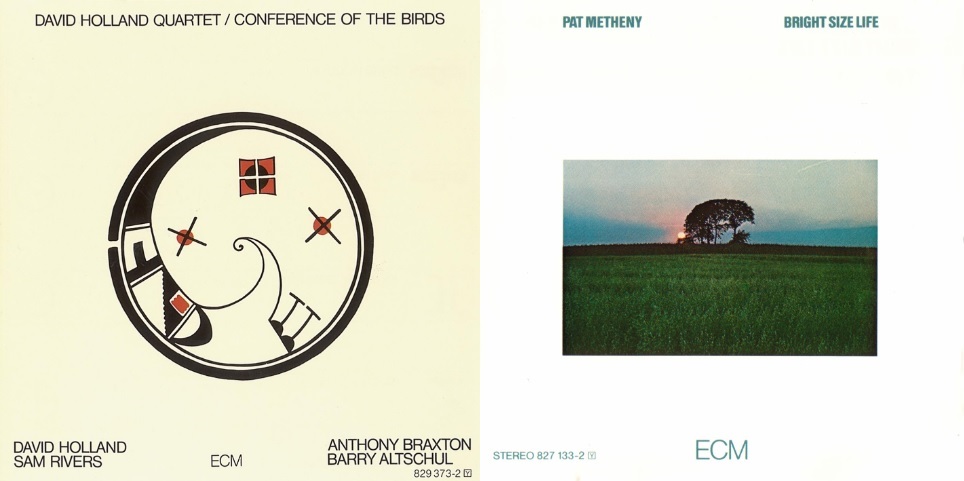

As my music collection is somewhere above 2,000 albums, pin-pointing exact dates of purchase or discovery of each item gets more difficult by the year. Thankfully, my discovery of ECM was early enough into my jazz foray that I have fond memories in learning more about this once-foreign music style. My starting point with ECM must have been the Dave Holland (his native land, just in case I need to reiterate, not being mainland Europe) album Conference of the Birds, which like some other of my earliest jazz listens was a library borrow. I didn’t fully embrace it at the time since my music tastes were still more guitar-focused, but I was slowly getting there. It was easier on my ears than another library rental I grabbed around that time in Bitches Brew by Miles Davis, but could still be pretty off the wall at times. I think the issue was the lead-off duo of “Four Winds” and “Q&A” being hard for me to grasp (the latter track particularly), and I lacked the patience to understand it fully. However, the album mellowed out soon after. The title track melody played by wind instrumentalists Anthony Braxton and Sam Rivers made the biggest impression on me and continues to be my main takeaway from the album, with Holland providing magnificent counter-melody (Barry Altschul rounds out the album’s lineup on percussion). That song in particular I found to be reminiscent of Vince Guaraldi’s theme to the Peanuts special It’s the Easter Beagle, Charlie Brown, which helped endear it to me. It wound up taking me a few years before I obtained my own copy, but it continues to be welcome ear candy as a recording I’d say makes for as worthy a starting point as any. It’s a well-balanced listen when you throw in another quasi-mellow tune in “Now Here (Nowhere)”, and it’s good to get you acclimatized (some might say radicalized) into enjoying freer forms of jazz without getting in too far over your head.

The next ECM album for me must have been Bright Size Life by American guitarist Pat Metheny, which would have likely been heard by me in the same year as Holland’s album. I appreciated it more initially than Conference of the Birds as I found bassist Jaco Pastorious’ playing easier to comprehend at a young age as I, too, played electric bass rather than upright bass. It also happened to be an easier Metheny album to grasp as my ear wasn’t initially receptive to some of the synth guitars used in many recordings I’d sampled from the ‘80s and ‘90s. I asked for it as a Christmas gift despite only hearing this album’s title track in a jazz guitar compilation box set my brother owned called Progressions: 100 Years of Jazz Guitar. Bright Size Life had the added bonus of introducing me to the great Ornette Coleman, as they covered his work in “Round Trip / Broadway Blues”.

Those albums have rather laid-back qualities while simultaneously having a healthy sense of adventure, which I feel which I feel aids both in demonstrating what some might call the “ECM sound” or dub as “ECM jazz” as if a sub-genre on its own. I’m not sure how accurate or helpful that using those terms truly is, given that each artist’s identity is their own, whether they found their voices prior to joining the label or continuing a similar trajectory creatively after departing the label. Without looking too deeply into what others really mean by the term, I’d say it’s just more from a recording process and production standard that remains sky-high. It’s difficult to describe precisely what I mean, but when I listen to an ECM album, the performances never sound confined. It’s as if each of them were recorded in as big a room as possible, with little in the way of studio trickery going on. What you hear is what you get: very natural sounds. Even if you take into account musicians that experiment in newer technology of their time that may seem less organic or acoustic-sounding (like how Metheny later made strong use of synthesized guitars and the Synclavier on albums like Offramp), they would do so in good taste to serve the compositions rather than act as a demo for pricey equipment. In summary, their best productions can sound as if the musicians are right in your home, though this is not a quality exclusive to the record label or to jazz or classical artists. You could make a case that an album like Spirit of Eden by Talk Talk puts forth that roomy ECM vibe.

Your introductions to ECM may be drastically different from mine, and some of the bigger names on the label are the realistic beginning place for many, such as with Keith Jarrett and The Köln Concert. It is apparently both the highest-selling jazz solo album and piano album of any style, as mentioned in this article on The Guardian. The Wikipedia page of the album lists sales as high as 4 million, though I can’t confirm an exact amount. Checking with certification sources for large markets such as RIAA, BPI, and BVMI, the record doesn’t show up, so perhaps the appeal is spread more evenly throughout the globe if the figure holds true. I will usually lean towards albums that have at least two musicians to work off one another, but when it’s just one person and a single instrument, it can lead to a whole other dimension in their playing. There’s some vulnerability in the knowledge that all the output is yours and yours alone, with the only restrictions being self-imposed. And to do it all live, where execution and inventiveness are vital in keeping a captive audience? I couldn’t imagine being able to pull it off, particularly long enough to span two vinyl records. It doesn’t take a jazz fan or a musician to listen to this concert and walk away having felt like you’ve been taken on a significantly impactful journey, one that may not have happened at all. Charles Waring compiles an effective summary of the concert in an article on UdiscoverMusic.com, which includes Keith’s overcoming a lack of sleep due to back pain in addition to being provided a far inferior piano to the one requested. Further, more technical details of Jarrett’s playing can be read on this 40th anniversary piece written by Bill Janovitz of The Observer. With as much praise and attention as the concert has received over the years, who knows how different the performance would have been had they managed to catch Keith on a good day!

Crystal Silence is also up there as well among ECM’s “big” albums, a duet record between vibraphonist Gary Burton and pianist Chick Corea. This was how I first learned about Burton (I have since acquired a number of his albums), but I was well familiar with Chick by the time I heard Crystal Silence. A Down Beat magazine review (August 16, 1973 issue) rated it five-stars, noting that “Burton’s playing always seems to take on a little extra something” in instances when he joins forces with a new or infrequent collaborator. The album’s praise led to the duo hooking up numerous other times throughout their careers, including 2008’s The New Crystal Silence, where they revisit in a live setting many of the compositions from the original album among the thirteen tracks. The ECM era was a rather interesting one in Corea’s career. Fresh of a high-profile stay with Miles Davis, he continued to explore the more experimental and avant-garde spectrum of jazz music. Among his work would be the Circle project that also featured three-quarters of the Conference of the Birds lineup (fellow ex-Miles musician Dave Holland, along with Braxton and Altschul), as well as a series of solo improvisational albums. Chick also launched the band Return to Forever through this label, with the moniker starting out as an album name only. Far from the controlled electric mayhem they would become notorious for across the likes of Hymn of the Seventh Galaxy and Romantic Warrior, the Return to Forever lineup had a different instrumental flavour with flute and sax by Joe Farrell instead of guitar, not to mention Flora Purim’s inclusion in a project that would later exclude vocals.

Jan Garbarek was a name I had once seen referenced in an introductory jazz book I had purchased at a library book sale (the name of the book escapes me). Little to my knowledge, he was one of ECM’s most prolific artists, having performed on well over 100 albums released by the label. Still, uncertain of where to begin, I bought the first album of his that I was able to locate in Officium. Officium brings together Garbarek, a sax player, accompanying The Hilliard Ensemble, a British male vocal quartet. It feels very much like a religious experience to listen to, a recording that I’d have a feeling that my grandmother would have enjoyed despite not being much of a jazz fan to the best of my knowledge. Not that I’d label this one a jazz album at all despite what Garbarek built his reputation playing. The album is unlike any other recording in my current collection. The only thing I owned that I could loosely associate it with was Colin Stetson, full of intriguing atmosphere and thought-provoking sounds fitting of a movie score. And since my purchase of Officium around a decade ago, I have heard “Regnantem Sempiterna” played on an episode of the Devs miniseries, so it’s gone at least as far as the small-screen. Much like the case with Corea and Burton, the success of this union brought about reunions with 1999’s Mnemosyne and 2010’s Officium Novum.

Coming back to ECM in general, uniformity in album sleeve design is an aspect of the label that I greatly enjoy. The odd outlier does exist, but the bulk of them feature visuals by a rather consistent roster of talent including Roberto Masotti, Singe Mähler, Frieder Grindler, Jan Krice, Woong Chul An, and Barbara Wojirsch among others. The choices of artwork and tends to have a very distinct look to it, often capturing one of nature’s beautiful scenes or still-life photography, with a large majority of it (particularly in the past twenty or so years) even going as far as using the same fonts on the covers. Some may think having an over-arching theme for covers is either redundant or a bit drab, but I think you’d have to search long and hard for one on ECM that doesn’t pair well with the music. I enjoy flipping through art books of various forms, and one of the big publishers of such works is Taschen. Their volumes are often categorized by individual visual artists, though there are themed editions that even span into the world of album covers. To my disappointment, their Jazz Covers collection only included two covers of ECM releases, Keith Jarrett’s Facing You and Paul Motian’s Conception Vessel (a great album!), and their genre-spanning 1000 Record Covers collection hardly contained any jazz at all. Thankfully, ECM does have some book offerings in Sleeves of Desire and Windfall Light: The Visual Language of ECM, both of which are published by Lars Müller. Even if you aren’t as big on the label’s music as I am, you may still find enjoyment on their visual offerings in these collections.

Affordability of their back catalog is another aspect that keeps bringing me back to the label, particularly on the second-hand vinyl market. While I believe that ECM should be mentioned in the same sentence as the likes of Blue Note, Verve, and Impulse, record collectors aren’t often in agreement, and price albums accordingly. I will say that sellers are starting to get wise to the label’s quality, but deals are still out there. Among my earlier ECM buys was a sampler that opened my ears even further after some of my initial discoveries. They released these in several volumes, and the one I lucked out in finding was the eighth one, which I grabbed for around two dollars. This edition contained tracks by Eberhard Weber, Keith Jarrett, Steve Swallow, Ralph Towner, and Chick Corea with Gary Burton. I wasn’t introduced to all of these artists at the time of purchase, but appreciated hearing more work of Swallow (who I was already familiar with through non-ECM releases Deconstructed and Real Book) and hearing Weber for the first time. Though ECM Sampler 8 happened to be one of the editions with the least variety, of which there were at least 11 volumes based on my research, I’m still glad to own it. The compilations don’t end with the Sampler series, mind you. These appeared in other forms like ECM Presents, ECM Special III – New Music In Guitar, and on CD the Suite For Sampler series if that’s your preferred format. Though such compilations may seem like an obsolete practice in the internet and streaming age, it’s well worth looking out for some of these collections because it’s a bit of a crap-shoot that you can locate authorized music uploaded to YouTube, Spotify, or other similar services from much of ECM’s history. In my case, that Suite For Sampler from 2000 would be intriguing because all of Gianluigi Trovesi, Bobo Stenson, Nils Petter Molvaer, Vassilis Tsabropoulos, Ketil Bjornstad, and Peter Rundel are new to me.

For those that wish to take a bigger bite out of the label’s discography by doing so in fewer individual purchases, ECM have a box set line titled Old and New Masters that bundles multiple albums of a single artist together in one package. From this series, I’ve grabbed John Abercrombie’s The First Quartet, which captures three albums from the guitarist’s quartet from 1979 through 1981 (featuring Richie Beirach, George Mraz, and Peter Donald), as well as four-CD set of drummer Peter Erskine’s trio (As It Was) from the 1990s, which featured John Taylor on piano and Palle Danielsson on bass. I’ve been eyeing the The Codona Trilogy set for a while, which contains three albums by the trio of Don Cherry, Collin Walcott, and Nanà Vasconcelos, and many others in this series seem well-worth the investment despite already owning an album or two within some of the sets.

I doubt I even have more than one or two percent of the label’s recordings, though having as little as ten percent of their back catalog would still make for a rather impressive collection. Even as I laid the seeds to finally getting around to writing an ECM discussion months ago, I found more and more on their label that I plan to invest some time, money, and attention on, such as Wolfgang Muthspiel and Tord Gustavsen. While I continue to explore the rich depth of music that Eicher and company have released, I’ll refer you to a few more sources that seem worthy of attention. First, there’s the documentary about Eicher titled Sounds and Silence: Travels with Manfred Eicher, which seems to be more of a day in the life close-up of the producer. Unfortunately, the version I viewed lacked subtitles, so it seems you may have to be fluent in German and possibly French to get the most out of it, though perhaps a subtitled version does exist. Nonetheless, the visuals and audio still tell a good story to capture his work with classical and orchestral musicians as well as jazz, and I always love seeing musicians in the act of creating and recording. Aside from the art books about ECM, Horizons Touched: The Music of ECM looks to be a broader examination of the label. While I’ve sworn off buying books for as long as I can until I’ve read the ones I currently own, this one sure looks tempting to hunt down!

To conclude, as everyone’s tastes differ, there are a wide variety of video discussions on YouTube regarding other music fans’ favourite releases from the German record label. Perhaps one of the following video creators can help guide your ears: